content:

LETTERS from......

Introduction

I.The Return

II.Tell No Man

III.Guarding the Door

IV - 4 - A Cloud on the Mirror

V. -5 - The Promise of Things Untold

VI - 6 -The Wand of Will

VII- 7- A Light behind the Veil

VIII - 8 - The Iron Grip of Matter

IX - 9 - Where Souls go up and down.

X - 10 - A Rendezvous in the Fourth Dimension

XI - 11 - The Boy–Lionel

XII - 12 - The Pattern World

XIII - 13 - Forms Real and Unreal

XIV - 14 - A Folio of Paracelsus

XV - 15 - A Roman Toga

XVI - 16 - A Thing to be forgotten

XVII - 17 - The Second Wife over there

XVIII - 18 - Individual Hells

XIX - 19 - A little Home in Heaven

XX - 20 - The Man who found God

XXI - 21 - The Leisure of the Soul

XXII - 22 - The Serpent of Eternity

XXIII - 23 - A Brief for the Defendant

XXIV - 24 - Forbidden Knowledge

XXV - 25 - A Shadowless World

XXVI - 26 - Circles in the Sand

XXVII - 27 - The Magic Ring

XXVIII - 28 - Except ye be as Little Children

XXIX - 29 - An Unexpected Warning

XXX - 30 - The Sylph and the Magician

XXXI - 31 - A problem in Celestial Mathematics

XXXII - 32 - A Change of Focus

XXXIII - 33 - Five Resolutions

XXXIV - 34 - The Passing of Lionel

XXXV - 35 - The Beautiful Being

XXXVI - 36 - The Hollow Sphere

XXXVII - 37 - An Empty China Cup

XXXVIII - 38 - Where Time is not

XXXIX - 39 - The Doctrine of Death

XL - 40 - The Celestial Hierarchy

XLI - 41 - The Darling of the Unseen

XLII - 42 - A Victim of the Non-existent

XLIII - 43 - A Cloud of Witnesses

XLIV - 44 - The Kingdom Within

XLV - 45 - The Game of Make-believe

XLVI - 46- Heirs of Hermes

XLVII - 47- Only a Song

XLVIII - 48- Invisible Gifts at Yuletide

XLIX - 49 - The Greater Dreamland

L - 50 - A Sermon and a Promise

LI - 51 - The April of the World

LII - 52 - A Happy Widower

LIII - 53 - The Archives of the Soul

LIV - 54 - A Formula for Mastership |

| |

| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

ONE

night last year in Paris I was strongly impelled to take up a pencil and

write, though what I was to write about I had no idea. Yielding to the

impulse, my hand was seized as if from the outside, and a remarkable

message of a personal nature came, followed by the signature “X.” ONE

night last year in Paris I was strongly impelled to take up a pencil and

write, though what I was to write about I had no idea. Yielding to the

impulse, my hand was seized as if from the outside, and a remarkable

message of a personal nature came, followed by the signature “X.”

The purport of the message was clear, but the signature puzzled me.

The following day I showed this writing to a friend, asking her if she had

any idea who “X” was.

“Why,” she replied, “don’t you know that that is what we always call Mr.

——?”

I did not know.

Now, Mr. —— was six thousand miles from Paris, and, as we supposed, in the

land of the living. But a day or two later a letter came to me from

America, stating that Mr. —— had died in the western part of the United

States, a few days before I received in Paris the automatic message signed

“X.”

So far as I know, I was the first person in Europe to be informed of his

death, and I immediately called on my friend to tell her that “X” had

passed out. She did not seem surprised, and told me that she had felt

certain of it some days before, when I had shown her the “X” letter,

though she had not said so at the time.

Naturally I was impressed by this extraordinary incident.

“X” was not a spiritualist. I am not myself, and never have been, a

spiritualist, and, so far as I can remember, only two other supposedly

disembodied entities had ever before written automatically through my

hand. This had happened when I was in the presence of a mediumistic

person; but the messages were brief, and I had not attached any great

importance to the phenomena.

In childhood I had several times put my hand upon a planchette with the

hand of another person, and the planchette had written the usual

trivialities. On one occasion, some months before the first “X” letter, I

had put my hand upon a planchette with the hand of a non-professional

medium, and the prophecy of a fire in my house during a certain month in

the following year was written, supposedly by a dead friend, which

prophecy was literally verified, though the fire was not caused by my

hand, nor was it in my own apartment.

A few times, years before, I had been persuaded by friends to go with them

to professional séances, and had seen so-called materializations. I had

also seen independently a few appearances which I could not account for on

any other hypothesis than that of apparitions of the dead.

But to the whole subject of communication between the two worlds I felt an

unusual degree of indifference. Spiritualism had always left me quite cold,

and I had not even read the ordinary standard works on the subject.

Nevertheless, I had for a number of years almost daily seen “hypnagogic

visions,” often of a startlingly prophetic character; and the explanation

of them later given by “X” may be the true explanation.

Soon after my receipt of the letter from American stating that Mr. —— was

dead, I was sitting in the evening with the friend who had told me who “X”

was, and she asked me if I would not let him write again—if he could.

I consented, more to please my friend than form any personal interest, and

the message beginning, “I am here, make no mistake,” came through my hand.

It came with breaks and pauses between the sentences, with large and badly

formed letters, but quite automatically, as in the first instance. The

force used on this occasion was such that my right hand and arm were lame

the following day.

Several letters signed “X” were automatically written during the next few

weeks; but, instead of becoming enthusiastic, I developed a strong

disinclination for this manner of writing, and was only persuaded to

continue it through the arguments of my friend that if “X” really wished

to communicate with the world, I was highly privileged in being able to

help him.

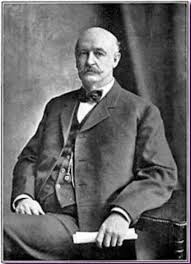

“X” was not an ordinary person. He was a well-known lawyer nearly seventy

years of age, a profound student of philosophy, a writer of books, a man

whose pure ideals and enthusiasms were an inspiration to everyone who knew

him. His home was far from mine, and I had seen him only at long intervals.

So far as I remember, we had never discussed the question of post-mortem

consciousness.

Gradually, as I conquered my strong prejudice against automatic writing, I

became interested in the things which “X” told me about the life beyond

the grave. I had read practically nothing on the subject, not even the

popular Letters from Julia, so I had no preconceived ideas.

The messages continued to come. After a while there was no more lameness

of the hand and arm, and the form of the writing became less irregular,

though it was never very legible.

For a time the letters were written in the presence of my friend, then “X”

began to come always when I was alone. He wrote either in Paris or in

London, as I went back and forth between those two cities. Sometimes he

would come several times a week; again, nearly a month would elapse

without my feeling his presence. I never called him, nor did I think much

about him between his visits. During most of the time my pen and my

thoughts were occupied with other matters.

Only in one instance before the writing began had I any idea as to what

the letter would contain. One night as I took up the pencil I knew what

“X” was going to write about; but, though I remember the incident, I have

forgotten to which message it referred.

While writing these letters I was generally in a state of

semi-consciousness, so that, until I read the message over afterwards, I

had only a vague idea of what it contained. In a few instances I was so

near unconsciousness that as I laid down the pencil I had not the remotest

idea of what I had written; but this did not often happen.

When it was first suggested that these letters should be published with an

introduction by me, I did not take very enthusiastically to the idea.

Being the author of several books, more or less well know, I had my little

vanity as to the stability of my literary reputation. I did not wish to be

known as an eccentric, a “freak.” But I consented to write an introduction

stating that the letters were automatically written in my presence, which

would have been the truth, though not all the truth. This satisfied my

friend; but as time went on, it did not satisfy me. It seemed not quite

sincere.

I argued the matter out with myself. If, I said, I publish these letters

without a personal introduction, they will be taken for a work of fiction,

of imagination, and the remarkable statements they contain will thus lose

all their force as convincing arguments for the truth of a hereafter. If I

write an introduction stating that they came by supposedly automatic

writing in my presence, the question will naturally arise as to whose hand

they came through, and I shall be forced to evasion. But if I frankly

acknowledge that they came through my own hand, and state the facts

exactly as they are only two hypotheses will be open: first, that they are

genuine communications from the disembodied entity; second, that they are

lucubrations of my own subconscious mind. But this latter hypothesis does

not explain the first letter signed “X,” which came before I knew that my

friend was dead; does not explain it unless it be assumed that the

subconscious mind of each person knows everything. In which case, why

should my subconscious mind set out upon a long and laborious deception of

me, on a premise which had not been suggested to it by my own objective

mind, or that of any other person?

That anyone would accuse me of deliberate deceit and romancing in so

serious a matter did not then and does not now seem likely, my fancy

having other and legitimate outlets in poetry and fiction.

The letters were probably two-thirds written before this question was

finally settled; and I decided that if I published the letters at all, I

should publish them with a frank introduction, stating the exact

circumstances of their reception by me.

The actual writing covered a period of more than eleven months. Then came

the question of editing. What should I leave out? What should I include? I

determined to leave out nothing except personal references to “X’s”

private affairs, to mine, and to those of his friends. I have not added

anything. Occasionally, when “X’s” literary style was clumsy, I have

reconstructed a sentence or cut out a repetition; but I have taken far

less liberty than I used, as an editor, to take with ordinary manuscripts

submitted to me for correction.

Sometimes “X” is very colloquial, sometimes he uses legal phraseology, or

American slang. Often he jumps from one subject to another, as one does in

friendly correspondence, going back to his original subject without a

connecting phrase.

He has made a few statements relative to the future life which are

directly contrary to the opinions which I have always held. These

statements remain as they were written. Many of his philosophical

propositions were quite new to me. Sometimes I did not see their

profundity until months afterwards.

I have no apology to offer for the publication of these letters. They are

probably an interesting document, whatever their source may be, and I give

them to the world with no more fear than when I gave my hand to “X” in the

writing of them.

If anyone asks the question, What do I myself think as to whether these

letters are genuine communications from the invisible world, I should

answer that I believe they are. In the personal and suppressed portions

reference was often made to past events and to possessions of which I had

no knowledge, and these references were verified. This leaves untouched

the favourite telepathic theory of the psychologists. But if these letters

were telepathed to me, by whom were they telepathed? Not by my friend who

was present at the writing of many of them, for their contents were as

much a surprise to her as to me.

I wish, however, to state that I make no scientific claims about this

book, for science demands tests and proofs. Save for the first letter

signed “X” before I knew that Mr. —— was dead, or knew who “X” was, the

book was not written under “test conditions,” as the psychologists

understand the term. As evidence of a soul’s survival after bodily death,

it must be accepted or rejected by each individual according to his or her

temperament, experience, and inner conviction as to the truth of its

contents.

In the absence of “X” and without some other entity on the invisible side

of Nature in whom I had a like degree of confidence, I could not produce

another document of this kind. Against indiscriminate mediumship I have

still a strong and ineradicable prejudice, for I recognise its dangers

both of obsession and deception. But for my faith in “X” and the faith of

my Paris friend in me, this book could never have been. Doubt of the

invisible author or of the visible medium would probably have paralysed

both, for the purposes of this writing.

The effect of these letters on me personally has been to remove entirely

any fear of death which I may ever have had, to strengthen my belief in

immortality, to make the life beyond the grave as real and vital as the

life here in the sunshine. If they can give even to one other person the

sense of exultant immortality which they have given to me, I shall feel

repaid for my labour.

To those who may feel inclined to blame me for publishing such a book I

can only say that I have always tried to give my best to the world, and

perhaps these letters are one of the best things that I have to give.

ELSA BARKER.

London, 1913.

LETTER I

THE RETURN

I AM here, make no mistake.

It was I who spoke before, and I now speak again.

I have had a wonderful experience. Much that I had forgotten I can now

remember. What has happened was for the best; it was inevitable.

I can see you, though not very distinctly.

I found almost no darkness. The light here is wonderful, far more

wonderful than the sunlight of the South.

No, I cannot yet see my way very well around Paris; everything is

different. It is probably by reason of your own vitality that I am able to

see you at this moment.

LETTER II

tell no man

I AM opposite to you now in actual space; that is, I am directly in front

of you, resting on something which is probably a couch or divan.

It is easier to come to you after dark.

I remembered on going out that you might be able to let me speak through

your hand.

I am already stronger. It is nothing to fear––this change of condition.

I cannot tell you yet how long I was silent. It did not seem long.

It was I who signed “X.” The Teacher helped me to make the connexion.

You had better tell no one for a while, except —––, that I have come, as I

do not want any obstructions to my coming when and where I will. Lend me

your hand sometimes; I will not misuse it.

I am going to stay out here until I am ready to come back with power.

Watch for me, but not yet.

Things seem easier to me now than they have seemed for a long time. I

carry less weight. I could have held on longer in the body, but it did not

seem worth the effort.

I have seen the Teacher. He is near. His attitude to me is very comforting.

But I would like to go now. Good night.

LETTER III

guarding the door

YOU need to take certain precautions to protect yourself against those who

press round me.

You have only to lay a spell upon yourself night and morning. Nothing can

get through that wall—nothing which you forbid your soul to entertain.

Do not let any of your energy be sucked out of you by these larvæ of the

astral world. No, they cannot annoy me, for I am now used to the idea of

them. You have absolutely nothing to fear, if you protect yourself.

LETTER IV - 4

a cloud on the mirror

(After a sentence had been half written, the writing suddenly stopped, and

was continued later.)

WHEN you respond to my call, wipe clean your mind as a child wipes its

slate when ready for a new maxim or example by its teacher. Your lightest

personal thought or fancy may be as a cloud upon a mirror, blurring the

reflection.

You can receive letters by this means, provided your mind does not begin

to work independently, to question in the midst of the writing.

I was not stopped this time, as before, by beings gathering round; but by

your own curiosity as to the end of an unusual sentence. You suddenly

became positive instead of negative, as if the receiving instrument in a

telegraph office should begin to send a message of its own.

I have learned here the reason for many psychic things which formerly

puzzled me, and I am determined if possible to protect you from the danger

of cross-currents in this work.

There was one night when I called and you would not let me in. Was that

kind?

But I am not reproaching you. I shall come again and again, until my work

is done.

I will come to you in a dream before long, and will show you many things.

LETTER V - 5

the promise of things untold

AFTER a time I will share with you certain knowledge that I have gained

since coming out. I see the past now as through an open window. I see the

road by which I have come, and can map out the road by which I mean to go.

Everything seems easy now. I could do twice as much work as I do–I feel so

strong.

As yet I have not settled down anywhere, but am moving about as the fancy

takes me; that is what I always dreamed of doing while in the body, and

never could make possible.

Do not fear death; but stay on earth as long as you can. Notwithstanding

the companion-ship I have here, I sometimes regret my failure in holding

on to the world. But regrets have less weight on this side–like our bodies.

Everything is well with me.

I will tell you things that have never been told.

LETTER VI -6

the wand of will

NOT yet do you grasp the full mystery of will. It can make of you anything

you choose, within the limit of your unit energy, for everything is either

active or potential in the unit of force which is man.

The difference between a painter and a musician, or between a poet and a

novelist, is not a difference of qualities in the entity itself; for each

unit contains everything except quantity, and thus has the possibilities

of development along any line chosen by its will. The choice may have been

made ages ago. It takes a long time, often many lives, to evolve an art or

a faculty for one particular kind of work in preference to all others.

Concentration is the secret of power, here as elsewhere.

As to the use of will-power in your present everyday problems, there are

two ways of using the will. One may concentrate upon a definite plan, and

bring it into effect or not according to the amount of force at one’s

disposal; or one may will that the best and highest and wisest plan

possible shall be demonstrated by the subconscious forces in the self and

in other selves. The latter is a commanding of all environment for a

special purpose, instead of commanding, or attempting to command, a

fragment of it.

In this communion between the outer and the inner worlds, you in the outer

world are apt to think that we in ours know everything. You expect us to

prophesy like fortune-tellers, and to keep you informed of what is passing

on the other side of the globe. Sometimes we can; generally we cannot.

After a while I may be able to enter your mind as a Master does, and to

know all the antecedent thoughts and plans in it; but now I cannot always

do so.

For instance, one night I looked everywhere for—and could not find him.

Perhaps it is necessary for you to think strongly of us, to make the way

easiest.

I am learning all the time. The Teacher is very active in helping me.

When I am absolutely certain of my hold upon your hand, I shall have much

to say about the life out here.

LETTER VII -7

a light behind the veil

MAKE an opening for me sometimes in the veil of dense matter that shuts

you from my eyes. I see you often as a spot of vivid light, and that is

probably when your soul is active with feeling or your mind keen with

thought.

I can read your thoughts occasionally, but not always. Often I try to draw

near, and cannot find you. You could not always find me, perhaps, should

you come out here.

Sometimes I am all alone: sometimes I am with others.

Strange, but I seem to myself to have quite a substantial body now, though

at first my arms and legs seemed sprawling in all directions.

As a rule, I do not walk about as formerly, nor do I fly exactly, for I

have never had wings; but I manage to get over space with incredible

rapidity. Sometimes, though, I walk.

Now, I want you to do me a favour. You know what a difficult job I often

had to keep things going, yet I kept them going. Don’t you get discouraged

about the material wherewithal for your work. Work right ahead, as if the

supply were there, and it will be there. You can demonstrate it in one way

or another. Do not feel weak or uncertain, for when you do you drag me

back to earth by force of sympathy. It is as bad as grieving for the dead.

LETTER VIII -8

the iron grip of matter

TO a man dwelling in the “invisible” there comes a sudden memory of earth.

“Oh!” he says. “The world is going on without me. What am I missing?”

It seems almost an impertinence on the part of the world to go on without

him. He becomes agitated. He is sure that he is behind the times, left out,

left over.

He looks about him, and sees only the tranquil fields of the fourth

dimension. Oh, for the iron grip of matter once more! To hold something in

taut hands!

Perhaps the mood passes, but one day it returns with redoubled force. He

must get out of the tenuous environment into the forcibly resistant world

of dense matter. But how?

Ah, he remembers! All action comes from memory. It would be a reckless

experiment had he not done it before.

He closes his eyes, reversing himself in the invisible. He is drawn to

human life, to human beings in the intense vibration of union. There is

sympathy here –– perhaps the sympathy of past experience with the souls of

those whom he now contacts, perhaps only sympathy of mood or imagination.

Be that as it may, he lets go his hold upon freedom and triumphantly loses

himself in the lives of human beings.

After a time he awakes, to look with bewildered eyes upon green fields and

the round, solid faces of men and women. Sometimes he weeps, and wishes

himself back. If he becomes discouraged, he may return –– only to begin

the weary quest of matter all over again.

If he is strong and stubborn, he remains and grows into a man. He may even

persuade himself that the former life in tenuous substance was only a

dream, for in dream he returns to it, and the dream haunts him and spoils

his enjoyment of matter.

After years enough he grows weary of the material struggle: his energy is

exhausted. He sinks back into the arms of the unseen, and men say again

with bated breath that he is dead.

But he is not dead. He has only returned whence he came.

LETTER IX -9

WHERE SOULS GO UP AND DOWN

My friend, there is nothing to fear in death. It is no harder than a trip

to a foreign country–the first trip–to one who has grown oldish and

settled in the habits of his own more or less narrow corner of the world.

When a man comes out here, the strangers whom he meets seem no more

strange than the foreign peoples seem to one who first goes among them. He

does not always understand them; there, again, his experience is like a

sojourn in a foreign country. Then, after a while, he begins to make

friendly advances and to smile with the eyes. The question, "Where are you

from?" meets with a similar response to that on earth. One is from

California, another is from Boston, another is from London. This is when

we meet on the highroads of travel; for there are lanes of travel over

here, where the souls go up and down as on the earth. Such a road is

generally the most direct line between two great centres; but it is never

on the line of a railway. There would be too much noise. We can hear

sounds made on the earth. There is a certain shock to the etheric ear

which carries the vibration of sound to us.

Sometimes one settles down for a long time in one place. I visited an old

home in the State of Maine, where a man on this aide of life had been

stopping for I do not know how many years; he told me that the children

had grown to be men and women, and that a colt to which he became attached

when he first came out had grown into a horse and had died of old age.

There are sluggards and dull people here, as with you. There are also

brilliant and magnetic people, whose very presence is rejuvenating.

It seems almost absurd to say that we wear clothes, the same as you do;

but we do not seem to need so many. I have not seen any trunks; but then I

have been here only a short time.

Heat and cold do not matter much to me now, though I remember at first

being rather uncomfortable by reason of the cold. But that is past.

LETTER X - 10

A RENDEZVOUS IN THE FOURTH DIMENSION

You can do so much for me by lending me your hand occasionally, the I

wonder why you shrink from it.

This philosophy will go on being taught in the world and all over the

world. Only a few perhaps, will reach the deeps of it in this life; but a

seed sown to-day may bear fruit long hence. Somewhere I have read that

grains of wheat which had been buried with mummies for two or three

thousand years had sprouted when placed in good soil in our own day. It is

so with a philosophic seed.

It has been said that he is a fool who works for philosophy instead of

making philosophy work for him; but a man cannot give to the world even a

little of a true philosophy without reaping sevenfold himself, and you

know the Biblical quotation which ends, "and in the world to come eternal

life." To get, one must give. That is the Law.

I can tell you many things about the life out here which may be of use to

others when they make the great change. Almost everyone brings memory over

with him. The men and women I have met and communed with have had more or

less vivid recollection of their earth life—that is, most of them.

I met one man who refused to speak of the earth, and was always talking

about "going on." I reminded him that if he went on far enough he would

come back to the place from which he started.

You have been curious, perhaps, as to what we eat and drink, if anything.

We certainly are nourished, and we seem to absorb much water. You also

should drink plenty of water. It feeds the astral body. I do not think

that a very dry body would ever have enough astral vitality to lend a hand

to a soul on this plane of life, as you are doing now. There is much

moisture in our bodies over here. Perhaps that is one reason why contact

with a so-called spirit sometimes gives warm-blooded persons a sense of

cold, and they shiver.

It is something of an effort on my part also to write like this, but it

seems to be worth while.

I come to the place where I feel that you are. I can see you better than

most others. Then I reverse; that is, instead of going in, as I used to

do, I go out with great force and in your direction. I take possession of

you by a strong propulsive effort.

Sometimes the writing has stopped suddenly in the midst of a sentence.

That was when I was not properly focussed. You may have noticed when

reversing and shutting away the outside world, that a sudden noise, or

maybe a wandering thought, would bring you right out again. It is so here.

Now, about this element in which we live. It undoubtedly has a place in

space, for it is all around the earth. Yes, every tree visible has its

invisible counterpart. When you, before sleep, come out consciously into

this world,1 you see things that exist, or have existed, in the material

world also. You cannot see anything in this world which has not a physical

counterpart in the other. There are, of course, thought-pictures,

imaginary pictures; but to see imaginatively is not to see on the astral

plane—not by any means. The things you see before going to sleep have real

existence, and by changing your rate of vibration you come out into this

world—or rather you go back into it, for you have to go in, in order to

come out.

1This undoubtedly refers to my "hypnagogic" visions.– ED.

Imagination has great power. If you make a picture in the mind, the

vibrations of the body may adjust to it if the will is directed that way,

as in thoughts of health or sickness.

It might be well as an experiment, when you want to come out here, to

choose a certain symbol and hold it before your eyes. I do not say that it

would help to change the vibration, but it might.

I wonder if you could see me if just before falling asleep you should come

out here with that thought and that desire dominant in your mind?

I am strong to-day, because I have been long with one who is stronger; and

if you want to make the experiment of trying to find me this night, I may

be able to help you better than at another time.

There is so much to say, and I can seldom talk with you. If you were

differently situated and quite free from other things, I could perhaps

come often. I am learning much that I should like to give you.

For instance, I think I can show you how to come out here at will, as the

Masters do constantly.

At first I took only your arm to write with, but now I get a better hold

of the psychic organisation. I saw that I was not working in the best way,

that there was a waste somewhere, so I asked the Teacher for instruction

in the matter. By this new method you will not feel so tired afterwards,

nor shall I.

I am going now, and will try to meet you in a few minutes. If the

experiment should fail, do not be discouraged; but try again some other

time. You will know me all right, if you do see me.

LETTER XI - 11

THE BOY–LIONEL

YOU will be interested to know that there are people out here, as on the

earth, who devote themselves to the welfare of others.

There is even a large organisation of souls who call themselves a League.

Their special work is to take hold of those who have just come out,

helping them to find themselves and to adjust to the new conditions. There

are both men and women in this League. They have done good service. They

work on a little—I do not want to say higher plane than the Salvation Army,

but rather a more intellectual plane. They help both children and adults.

It is interesting about the children. I have not had time yet to observe

all these things for myself; but one of the League workers tells me that

it is easier for children to adjust themselves to the changed life than it

is for grown persons. Very old people are inclined to sleep a good deal,

while children come out with great energy, and bring with them the same

curiosity that they had in earth life. There are no violent changes. The

little ones grow up, it is said, about as gradually and imperceptibly as

they would have grown on earth. The tendency is to fulfil the normal

rhythm, though there are instances where the soul goes back very soon,

with little rest. That would be a soul with great curiosity and strong

desires.

There are horrors out here—far worse than the horrors on earth. The decay

from vice and intemperance is much worse here than there. I have seen

faces and forms that were really frightful, faces that seemed to be

half-decayed and falling in pieces. These are the hopeless cases, which

even the League of workers I spoke about leave to their fate. It is

uncertain what the fate of such people will be; whether they will

reincarnate or not in this cycle, I do not know.

The children are so charming! One young boy is with me often; he calls me

Father, and seems to enjoy my society. He would be, I should think, about

thirteen years old, and he has been out here some time. He could not tell

me just how long, but I will ask him if he remembers the year, the

calendar year, in which he came out.

It is not true that we cannot keep our thoughts to ourselves if we are

careful to do so. We can guard our secrets, if we know how. That is done

by suggestion, or laying a spell. It is, though, much easier here than on

earth to read the minds of others.

We seem to communicate with one another in about the same way that you do;

but I find, as time goes by, that I converse more and more by powerful and

projected thought than by the moving of the lips. At first I always opened

my mouth when I had anything to say; it is easier now not to do so, though

I sometimes do it still by force of habit. When a man has recently come

out he does not understand another unless he really speaks; that is, I

suppose, before he has learned that he also can talk without using much

breath.

But I was telling you about the boy. He is all interest in regard to

certain things I have told him about the earth,—especially aeroplanes,

which were not yet very practicable when he came out. He wants to go back

and fly in a aeroplane. I tell him that he can fly here without one, but

that does not seem to be the same thing to him. He wants to get his

fingers on machinery.

I advise him not to be in any hurry about going back. The curious thing

about it is that he can remember other and former lives of his on earth.

Many out here have no more memory of their former lives, before the last

one, than they had while in the body. This is not a place where everyone

knows everything—far from it. Most souls are nearly as blind as they were

in life.

The boy was an inventor in a prior incarnation, and he came out this time

by an accident, he says. He should stay here a little longer, I think, to

get a stronger rhythm for a return. That is only my idea. I am so

interested in the boy that I should like to keep him, and perhaps that

influences my judgment somewhat.

You see, we are still human.

You asked me some questions, did you not? Will you speak them aloud? I can

hear.

Yes, I feel considerably younger than I have felt for a long time, and I

am well. At first I felt about as I did in my illness, with times of

depression and times of freedom from depression; but now I am all right.

My body does not give me much trouble.

I believe that old people grow younger here until they reach their prime

again, and that then they may hold that for a long time.

You see, I have not become all-wise. I have been able to pick up a good

deal of knowledge which I had forgotten; but about all the details of this

life I still have much to learn.

Your curiosity will help me to study conditions and to make inquiries,

which otherwise I might not have made for a long time, if ever. Most

people do not seem to learn much out here, except that naturally they

learn the best and easiest way of getting on, as in earth life.

Yes, there are schools here where any who wish for instruction can receive

it—if they are fit. But there are only a few great teachers. The average

college professor is not a being of supreme wisdom, whether here or there.

LETTER XII - 12

THE PATTERN WORLD

THERE is something I want to qualify in what I said the other day, that

there is nothing out here which has not existed on the earth. Since then I

have learned that that statement is not exactly true. There are strata

here. This I have learned recently. I still believe that in the lowest

stratum next the earth all or nearly all that exists has existed on earth

in dense matter. Go a little farther up, a littler farther away—how far I

cannot say by actual measurement; but the other night in exploring I got

into the world of patterns, the paradigms—if that is the word—of things

which are to be on earth. I saw forms of things which, so far as I know,

have not existed on your planet–inventions, for example. I saw wings that

man could adjust to himself. I saw also new forms of flying-machines. I

saw model cities, and towers with strange wing-like projections on them,

of which I could not imagine the use. The progress of mechanical invention

is evidently only begun.

Another time I will go on, farther up in that world of pattern forms, and

see if I can learn what lies beyond it.

Bear this in mind: I merely tell you stories, as an earthly traveller

would tell, of the things I see. Sometimes my interpretation of them may

be wrong.

When I was in the place which we will call the pattern world, I saw almost

nobody there—only an occasional lone voyager like myself. I naturally

infer from this that but few of those who leave the earth go up there at

all. I think from what I have seen, and from conversations I have had with

men and women souls, that most of them do not get very far from the earth,

even out here.

It is strange, but many persons seem to be in the regular orthodox heaven,

singing in white robes, with crowns on their heads and with harps in their

hands. There is a region which outsiders call "the heaven country."

There is also, they tell me, a fiery hell, with at least the smell of

brimstone; but so far I have not been there. Some day when I feel strong I

will look in, and if it is not too depressing I will go farther—if they

will let me.

For the present I am looking about here and there, and I have not studied

carefully any place as yet.

I took the boy, whose name by the way is Lionel, out with me yesterday.

Perhaps we ought to say last night, for your day is our night when we are

on your side of this great hollow sphere. You and the solid earth are in

the centre of our sphere.

I took the boy out with me for what you would call a walk.

First we went to the old quarter of Paris, where I used to live in a

former life; but Lionel could not see anything, and when I pointed out

certain buildings to him he asked me quite sincerely if I were dreaming. I

must have some faculty which is not generally developed among my fellow

citizens in the astral country. So when the boy found that Paris was only

a figment of my imagination—he used to live in Boston—I took him to see

heaven. He remarked:

"Why, this must be the place my grandmother used to tell me about. But

where is God?"

That I could not tell him; but, on looking again, we saw that nearly

everybody was gazing in one direction. We also gazed with the others, and

saw a great light, like a sun, only it was softer and less dazzling than

the material sun.

"That," I said to the boy, "is what they see who see God."

And now I have something strange to tell you; for, as we gazed at that

light, slowly there took form between us and it the figure which we are

accustomed to see represented as that of the Christ. He smiled at the

people and stretched out His hands to them.

Then the scene changed, and He had on His left arm a lamb; and then again

He stood as if transfigured upon a mountain; then He spoke and taught them.

We could hear His voice. And then He vanished from our sight.

LETTER XIII - 13

FORMS REAL AND UNREAL

WHEN I first came out here I was so interested in what I saw that I did

not question much as to the manner of the seeing. But lately—especially

since writing the last letter or two—I have begun to notice a difference

between objects that at a superficial glance seem to be of much the same

substance. For example, I can sometimes see a difference between those

things which have existed on earth unquestionably, such as the forms of

men and women, and other things which, while visualised and seemingly

palpable, may be, and probably are, but thought-creations.

This idea came to me while looking on at the dramas of the heaven country,

and it was forced upon me with greater power while making other and recent

explorations in that which I have called the pattern world.

Later I may be able to distinguish at a glance between these two classes

of seeming objects. For example, if I encounter here a being, or what

seems a being, and if I am told that it is some famous character in

fiction, such as Jean Valjean in Hugo's Les Misérables, I shall have

reason to believe that I have seen a thought-form of sufficient vitality

to stand alone, as a quasi-entity in this world of tenuous matter. So far

I have not encountered any such characters.

Of course, unless I were able to hold converse with a being, a form, or

saw others do so, I could not positively state that it had an essential

existence. Hereafter I shall often put things to the test in this way. If

I can talk to a seeming entity, and if it can answer me, I am justified in

considering it as a reality. A character in fiction, or any other mental

creation, however vivid as a picture, would have no soul, no unit of force,

no real self. Whatever comes to me merely as a picture I shall try to

submit to this test.

If I see a peculiar form of tree or animal, and can touch and feel it,—for

the senses here are quite as acute as those of earth,—I know that it

exists in the subtle matter of this plane.

I believe that all the beings whom I have seen here are real; but if I can

find one that is not,—a being which I cannot feel when I touch it and

which cannot respond to my questions,—I shall have a datum for my

hypothesis that thought-forms of beings, as well as things, may have

sufficient cohesion to seem real.

It is undoubtedly true that there is no spirit without substance, no

substance without spirit, latent or expressed; but a painting of a man may

seem at a distance to be a man.

Can there exist deliberate thought-creations here, deliberate and

purposive creations? I believe so. Such a thought-form would probably have

to be very intense in order to persist.

It seems to me that I had better settle this question to my own

satisfaction before talking any more about it.

LETTER XIV - 14

A FOLIO OF PARACELSUS

THE other day I asked my Teacher to show me the archives in which those

who had lived out here had recorded their observations, if such existed.

He said:

"You were a great reader of books when you were on the earth. Come."

We entered a vast building like a library, and I caught my breath in

wonder. It was not the architecture of the building which struck me, but

the quantities of books and records. There must have been millions of them.

I asked the Teacher if all the books were here. He smiled and said:

"Are there not enough? You can make your choice."

I asked if the volumes were arranged by subjects.

"There is an arrangement," he answered. "What do you want?"

I said that I should like to see the books in which were written the

accounts of explorations which other men had made in this (to me) still

slightly known country.

He smiled again, and took from a shelf a thick volume. It was printed in

large black type.1

1I hope no one will expect me to answer the question why should such a

book appear to be printed in large black type. I have no more idea than

has the reader.–Ed.

"Who wrote this book?" I asked.

"There is a signature," he replied.

I looked at the end and saw the signature: it was that used by Paracelsus.

"When did he write this?"

"Soon after he came out." It was written between his Paracelsus life and

his next one on earth."

The book which I had opened was a treatise on spirits, human, angelic, and

elemental. It began with the definition of a human spirit as a spirit

which had had the experience of life in human form; and it defined an

elemental spirit as a spirit of more or less developed self-consciousness

which had not yet had that experience.

Then the author defined an angel as a spirit of a high order which had not

had, and probably would not have in future, such experience in matter.

He went on to state that angelic spirits were divided into two sharply

defined groups, the celestial and the infernal, the former being those

angels who worked towards harmony with the laws of God, the latter being

those angels who worked against that harmony. But he said that both these

orders of angels were necessary, each to the other's existence; that if

all were good the universe would cease to be; that good itself would cease

to be through the failure of its opposite—evil.

He said that in the archives of the angelic regions there were cases on

record where a good angel had become bad or a bad angel had become good,

but that such cases were of rare occurrence.

He then went on to warn his fellow souls who should be sojourning in that

realm in which he then wrote, and in which I knew myself also to be,

against holding communion with evil spirits. He declared that in the

subtler forms of life there were more temptations than in the earth life;

that he himself had often been assailed by malignant angels who had urged

him to join forces with them, and that their arguments were sometimes

extremely plausible.

He said that while living on earth he had often had conversations with

spirits both good and bad; but that while on earth he had never, so far as

he knew, held converse with an angel of a malignant nature.

He advised his readers that there was one way to determine whether a being

of the subtler world was an angel or merely a human or an elemental

spirit, and that was by the greater brilliancy of the light which

surrounded an angel. He said that both good and bad angels were extremely

brilliant; but that there was a difference between them, perceptible at

the first glance at their faces; that the eyes of the celestial angels

were aflame with love and intellect, while the eyes of the infernal angels

were very unpleasant to encounter.

He said that it would be possible for an infernal angel to disguise

himself to a mortal, so that he might be mistaken for an angel of light;

but that it was practically impossible for an angel to disguise his real

nature from those souls who were living in their subtle bodies.

I will perhaps say more on this subject another night. I must rest now.

LETTER XV

A ROMAN TOGA

ONE thing which makes this country so interesting to me is its lack of

conventionality. No two persons are dressed in the same way—or no, I do

not mean that exactly, but many are so eccentrically dressed that their

appearance gives variety to the whole.

My own clothes are, as a rule, similar to those I wore on earth, though I

have as an experiment, when dwelling in thought on one of my long-past

lives, put on the garments of the period.

It is easy to get the clothes one wants here. I do not know how I became

possessed of the garments which I wore on coming out; but when I began to

take notice of such things, I found myself dressed about as usual. I am

not yet sure whether I brought my clothes with me.

There are many people here in costumes of the ancient days. I do not infer

from this fact that they have been here all those ages. I think they wear

such clothes because they like them.

As a rule, most persons stay near the place where they lived on earth; but

I have been a wanderer from the first. I go rapidly from one country to

another. One night (or day with you) I may take my rest in America; the

next night I may rest in Paris. I have spent hours of repose on the divan

in your sitting-room, and you did not know that I was there. I doubt,

though, if I could stay for hours in your house when I was myself awake

without your sensing my presence.

Do not think, however, from what I have just said, that it is necessary

for me to rest on the solid matter of your world. Not at all. We can rest

on the tenuous substance of our own world.

One day, when I had been here only a short time, I saw a woman dressed in

a Greek costume, and asked her where she got her clothes. She replied that

she had made them. I asked her how, and she said:

"Why, first I made a pattern in my mind, and then the thing became a

garment."

"Did you take every stitch?"

"Not as I should have done on earth."

I looked closer and saw that the whole garment seemed to be in one piece,

and that it was caught on the shoulders by jewelled pins. I asked where

she got the jewelled pins, and she said that a friend had given them to

her. Then I asked where the friend had got them. She told me that she did

not know, but that she would ask him. Soon after that she left me, and I

have not seen her since, so the question is still unanswered.

I began to experiment to see if I also could make things. It was then that

I conceived the idea of wearing a Roman toga, but for the life of me I

could not remember what a Roman toga looked like.

When next I met the Teacher I told him of my wish to wear a toga of my own

making, and he carefully showed me how to create garments such as I

desired: To fix the pattern and shape clearly in my mind, to visualise it,

and then by power to desire to draw the subtle matter of the thought-world

round the pattern, so as actually to form the garment.

"Then," I said, "the matter of the thought-world, as you call it, is not

the same kind of matter as that of my body, for instance?"

"In the last analysis," he answered, "there is only one kind of matter in

both worlds; but there is a great difference in vibration and tenuity."

Now the thought-substance of which our garments are formed seems to be an

extremely tenuous form of matter, while our bodies seem to be pretty

solid. We do not feel at all like transparent angels sitting on damp

clouds. Were it not for the quickness with which I get over space, I

should think sometimes that my body was as solid as ever.

I can often see you, and to me you seem tenuous. It is all, I suppose, the

old question of adjusting to environment. At first I could not do it, and

had some trouble in learning to adjust the amount of energy necessary for

each particular action. So little energy is required here to move myself

about that at first when I started to go a short distance—say, a few

yards—I would find myself a mile away. But I am now pretty well adjusted.

I must be storing up energy here for a good hard life when I return to the

earth again. The hardest work I do now is to come and write through your

hand, but you offer less and less resistance as time goes on. In the

beginning it took all my strength; now it takes only a comparatively small

effort. Yet I could not do it long at a time without using your own

vitality, and that I will not do.

You may have noticed that you are no longer fatigued after the writing,

though you used to be at first.

But I was speaking of the lack of conventionality out here. Souls hail

each other when they want to, without much ceremony. I have seen a few old

women who were afraid to talk to a stranger, but probably they had not

been here long and the earth habits still clung to them.

Do not think, however, that society here is too free and easy. It is not

that, but men and women do not seem to be so afraid of each other as they

were on earth.

LETTER XVI

A THING TO BE FORGOTTEN

I WANT to say a word to those who are about to die. I want to beg them to

forget their bodies as soon as possible after the change which they call

death.

Oh, the terrible curiosity to go back and look upon that thing which we

once believed to be ourselves! The thought comes to us now and then so

powerfully that it acts in a way against our will and draws us back to it.

With some it is a morbid obsession, and many cannot get free from it while

there remains a shred of flesh on the bones which they once leaned upon.

Tell them to forget it altogether, to force the thought away, to go out

into the other life free. Looking back upon the past is sometimes good,

but not upon this relic of the past.

It is so easy to look into the coffin, because the body which we wear now

is itself a light in a dark place, and it can penetrate grosser matter. I

have been back myself a few times, but am determined to go back no more.

Yet some day the thought may come to me again with compelling insistence

to see how it is getting on.

I do not want to shock or pain you—only to warn you. It is sad to see the

sight which inevitably meets one in the grave. That may be the reason why

many souls who have not been here long are so melancholy. They return

again and again to the place which they should not visit.

You know that out here if we think intently of a place we are apt to find

ourselves there. The body which we use is so light that it can follow

thought almost without effort. Tell them not to do it.

One day while walking down an avenue of trees—for we have trees here—I met

a tall woman in a long black garment. She was weeping—for we have tears

here also. I asked her why she wept, and she turned to me eyes of

unutterable sadness.

I have been back to it," she said.

My heart ached for her, because I knew how she felt. The shock of the

first visit is repeated each time, as the thing one sees is less and less

what we like to think of ourselves as being.

Often I remember that tall woman in black, walking down the avenue of

trees and weeping. It is partly curiosity that draws one back, partly

magnetic attraction; but it can do no good. It is better to forget it.

I have sometimes longed, from sheer scientific interest, to ask my boy

Lionel if he had been back to his body; but I have not asked him for fear

of putting the idea into his mind. He has such a restless curiosity.

Perhaps those who go out as children have less of that morbid instinct

than we have.

If we could only remember in life that the form which we call ourselves is

not our real immortal self at all, we would not give it such an

exaggerated importance, though we would nevertheless take needful care of

it.

As a rule, those who say that they have been long here do not seem old. I

asked the Teacher why, and he said that after a time an old person forgets

that he is old, that the tendency is to grow young in thought and

therefore young in appearance, that the body tends to take the form which

we hold of it in our minds, that the law of rhythm works here as elsewhere.

Children grow up out here, and they may even go on to a sort of old age if

that is the expectation of the mind; but the tendency is to keep the

prime, to go forward or back towards the best period, and then to hold

that until the irresistible attraction of the earth asserts itself again.

Most of the men and women here do not know that they have lived many times

in flesh. They remember their latest life more or less vividly, but all

before that seems like a dream. One should always keep the memory of the

past as clear as possible. It helps one to construct the future.

Those people who think of their departed friends as being all-wise, how

disappointed they would be if they could know that the life on this side

is only an extension of the life on earth! If the thoughts and desires

there have been only for material pleasures, the thoughts and desires here

are likely to be the same. I have met veritable saints since coming out;

but they have been men and women who held in earth life the saintly ideal,

and who now are free to live it.

Life can be so free here! There is none of that machinery of living which

makes people on earth such slaves. In our world a man is held only by his

thoughts. If they are free, he is free.

Few, though, are of my philosophic spirit. There are more saints here than

philosophers, as the highest ideal of most persons, when intensely active,

has been towards the religious rather than the philosophic life.

I think the happiest people I have met on this side have been the painters.

Our matter is so light and subtle, and so easily handled, that it falls

readily into the forms of the imagination. There are beautiful pictures

here. Some of our artists try to impress their pictures upon the mental

eyes of the artists of earth, and they often succeed in doing so.

There is joy in the heart of one of our real artists when a fellow

craftsman on your side catches an idea from him and puts it into execution.

He may not always be able to see clearly how well the second man works out

the idea, for it requires a special gift or a special training to see from

one form of matter into the other; but the inspiring spirit catches the

thought in the inspired one's mind, and knows that a conception of his own

is being executed upon the earth.

With poets it is the same. There are lovely lyrics composed out here and

impressed upon the receptive minds of earthly poets. A poet told me that

it was easier to do that with a short lyric than with an epic or a drama,

where a long-continued effort was necessary.

It is much the same with musicians. Whenever you go to a concert where

beautiful music is being played, there is probably all round you a crowd

of music-loving spirits, drinking in the harmonies. Music on earth is much

enjoyed on this side. It can be heard. But no sensitive spirit likes to go

near a place where bad strumming is going on. We prefer the music of

stringed instruments. Of all earthly things, sound reaches most directly

into this plane of life. Tell that to the musicians.

If they could only hear our music! I did not understand music on earth,

but now my ears are becoming adjusted. It seems sometimes as if you must

hear our music over there, as we hear yours.

You may have wondered how I spend my time and where I go. There is a

lovely spot in the country which I never tire of visiting. It is on the

side of a mountain, not far from my own city. There is a little road

winding round a hill, and just above the road is a hut, a roofed enclosure

with the lower side open. Sometimes I stay there for hours and listen to

the rippling of the brook which runs beside the road. The tall slender

trees have become like brothers to me. At first I cannot see the material

trees very clearly; but I go into the little hut which is made of fresh

clean boards with a sweet smell, and I lie down on the shelf or bunk along

the wall; then I close my eyes and by an effort—or no, it is not what I

would call an effort, but by a sort of drifting—I can see the beautiful

place. But you must know that this is in the night time there, and I see

it by the light of myself. That is why we travel in the dark part of the

twenty-four hours, for in the bright sunlight we cannot see at all. Our

light is put out by the cruder light of the sun.

One night I took the boy Lionel there with me, leaving him in the hut

while I went a little distance away. Looking back, I saw the whole hut

illuminated by a lovely radiance—the radiance of Lionel himself. The

little building, which has a peaked roof, looked like a pearl lighted from

within. It was a beautiful experience.

I then went to Lionel and told him to go in his turn a little distance

away, while I took his place in the hut. I was curious to know if he would

see the same phenomenon when I lay there, if I could shed such a light

through dense matter—the boards of the building. When I called him to me

afterwards and asked if he had seen anything strange, he said:

"What a wonderful man you are, Father! How did you make that hut seem to

be on fire?"

Then I knew that he had seen the same thing I had seen.

But I am tired now and can write no more. Good night, and may you have

pleasant dreams.

LETTER XVII

THE SECOND WIFE OVER THERE

I AM often called upon here to decide matters for others. Many people call

me simply "the Judge"; but we bear, as a rule, the name that we last bore

on earth.

Men and women come to me to settle all sorts of questions for them,

questions of ethics, questions of expediency, even quarrels. Did you

suppose that no one quarrelled here? Many do. There are even long-standing

feuds among them.

The holders of different opinions on religion are often hot in their

arguments. Coming here with the same beliefs they had on earth, and being

able to visualise their ideals and actually to experience the things they

are expecting, two men who hold opposite creeds forcibly are each more

intolerant than ever before. Each is certain that he is right and that the

other is wrong. This stubbornness of belief is strongest with those who

have been here only a short time. After a while they fall into a larger

tolerance, living their own lives more and more, and enjoying the world of

proofs and realisations which each soul builds for itself.

But I want to give you an illustration of the sort of questions on which I

am asked to pass judgment.

There are two women here who in life were both married to one man, though

not at the same time. The first woman died, then the man married again,

and soon—not more than a year or two after—the man and his second wife

both came out. The first wife considers herself the man's only wife, and

she follows him about everywhere. She says that he promised to meet her in

heaven. He is more inclined to the second wife, though he still feels

affection for Wife No. 1. He is rather impatient at what he calls her

unreasonableness. He told me one day that he would gladly give them both

up, if he could be left in peace to carry out certain studies in which he

is interested. These were among the people I met soon after I began to be

strong myself here—it was not so very long ago; and the man has sought my

society so much that the women, in order to be near him, have come along

too.

One day they all three came to me and propounded their question—or, rather,

Wife No. 1 propounded it. She said:

"This man is my husband. Should not, therefore, this other woman go far

away and leave him altogether to me?"

I asked Wife No. 2 what she had to say. Her answer was that she would be

all alone here but for her husband, and that as she had had him last, he

now belonged more to her than to the other.

In a flash the memory came to me of those Sadducees who propounded a

similar question to Christ, and I quoted His answer as nearly as I could

remember it: that "when they shall rise from the dead, they neither marry,

nor are given in marriage; but are as the angels which are in heaven."

My answer was as much a staggerer for them as their question had been for

me, and they went away to think about it.

When they were gone I began myself to ponder the question. I had already

observed that, whether or not all here are as the angels in heaven, there

does seem to be a good deal of mating and rejoining of former mates. The

sex distinction is as real here as on the earth, though, of course, its

expression is not exactly the same. I asked myself a good many questions

which perhaps would never have occurred to me but for the troubles of this

interesting triad, and I thought of the man I had somewhere read about,

who said that he never knew his own opinion of anything until he tried to

express it to somebody.

After a while the three came to me again and said that they had been

talking things over, perhaps after the manner of angels in heaven; for

Wife No. 1 told me that she had decided to "let" her husband spend a part

of his time with the other woman, if he wanted to.

Now, the man had a sweetheart, a girl sweetheart, before he had either of

his wives. The girl is out here somewhere, and the man often has a strong

desire to try to find her. What opportunity he will now have to do so, I

cannot say. The situation is rather depressing for the poor fellow. It is

bad enough to have one person who insists on every minute of your society,

without having two. And I think his case is not unusual. Perhaps the only

way in which he can get free from his two insistent companions is by going

back to the earth.

There is a way, however, by which he could secure solitude; but he does

not know of it. A man who knows how can isolate himself here as well as he

could on earth; he can build round himself a wall which only the eyes of a

great initiate can pierce. I have not told this secret to my friend; but

perhaps I shall some day, if it seems necessary for his development that

he have a little solitude. At present it seems to me that he will learn

more from adjusting to this double claim and trying to find the truth that

lies in it. Perhaps he may learn that really, essentially, fundamentally,

he does not "belong" to either of these women. The souls out here seem to

belong to themselves, and after the first few years they get to love

liberty so much that they are ready to yield a little of their claim upon

others.

This is a great place in which to grow, if one really wants to grow;

though few persons take advantage of its possibilities. Most are content

to assimilate the experiences they had on earth. It would be depressing to

one who did not realise that will is free, to see how souls let slip their

opportunities here, even as they did on the moon-guarded planet.

There are teachers here who stand ready to help anyone who wishes their

help in making real and deep studies in the the mysteries of life—the life

here, the life there, and in the remote past.

If a man understands that his recent sojourn on earth was merely the

latest of a long series of lives, and if he concentrates his mind towards

recovering the memories of the distant past, he can recover them. Some

persons may think that the mere dropping of the veil of matter should free

the soul from all obscuration; but, as on earth so out here, "things are

not thus and so because they ought to be, but because they are."

We draw to ourselves the experiences which we are ready for and which we

demand, and most souls do not demand enough here, any more than they did

in life. Tell them to demand more, and the demand will be answered.

LETTER XVIII

INDIVIDUAL HELLS

SOME time ago I told you of my intention to visit hell; but when I began

investigations on that line there proved to be many hells.

Each man who is not content with the orthodox hell of fire and brimstone

builds one out of the mind-stuff suited to his imaginative need.

I believe that men place themselves in hell, that no God puts them there.

I began looking for a hell of fire and brimstone, and found it. Dante must

have seen the same things I saw.

But there are other and individual hells––

(The writing suddenly stopped, for no apparent reason, and was not

continued that night.)

(much more on this theme in the old book A WANDERER IN THE SPIRIT LAND of Franchezzo

)

LETTER XIX

A LITTLE HOME IN HEAVEN

I HAVE met a very interesting man since last I wrote to you. He is a lover

who for ten years waited here for his love to come to him.

They said on earth that he was dead, and they urged her to love another;

but she could not forget him, for every night he met her soul in dreams,

every night she came out to him here, and sometimes she could recall on

waking all that he had said to her in sleep. She had told him that she

would not delay long in the sunshine world, but would come out to him in

the self-lighted world.

Only a little while ago she came. He had been long getting ready for her

coming, and had built in the substance of this world the little home he

had planned to build for her in the outer world.

He told me how one night when she came to him in dream, she said that she

would rejoin him on the morrow, never to leave him again. He was startled,

and would almost have stayed her; because he had died a sudden and painful

death, and he dreaded pain for her. Always he had watched over her,

warning her of danger; but this time he felt, after the first shock of the

message was over, that she was really coming. And he was very happy.

He had found no other love out here; for when one leaves the earth full of

a great affection, and when the earthly loved one does not forget, the tie

can hold for many years unweakened. You on the earth have forgotten so

much of what you learned here that you do not realise how your thought of

us can make us happy, do not realise how your forgetfulness of us can

throw us back entirely upon ourselves.

Often those who go farthest here, who really grow in spirituality, are

those whose loves have forgotten them on earth; but it is sad to be

forgotten, nevertheless.

It is a bitter power you make possible to us when you thus throw us back

upon ourselves; and not all souls are strong enough or aspiring enough to

make use of the lonely impetus that might help them to scale the ladder of

spiritual knowledge.

But to return to my lovers. All that day he remained near her. He would

not rest; for, as I have told you, we generally rest a little when the sun

shines on the earth. All that day he remained near her. He could not see

her body, for the rays of sunlight were too strong for him. But, after

hours of waiting, suddenly he felt a hand in his, and though she was

invisible to him yet he knew that she was here. And he spoke to her, using

such words as he would have used on earth. She did not seem to understand.

He spoke again, and still she did not answer; but he knew from the

pressure of her hand that she realised his presence. So hand in hand they

stood there in the darkness of the sunlight, the man able to speak because

of his long experience in this world of subtle sounds, the woman

speechless and bewildered, but still clinging to his hand.

When the sunshine went away he was able to see her face, and her eyes were

wide and frightened; but still she seemed held to the room in which lay

the body which had been she. It was summer, and the windows were open. He

sought to draw her away into the perfumed night which to them was day; but

she held his hand and would not let him go.

At last he drew her away a short distance and spoke to her again. Now she

heard and answered him.

"Beloved," she said, "which is I? For I see myself—I feel myself—back

there also. I seem to be in two places. Which I is really I?"

He comforted her with loving words. He was still afraid to caress her, for

the touch of souls is very keen, and he feared lest she should go back

into the form which seemed to be so near them, and thus be lost to him

again. But though she had often come to him in dreams, it had not been so

vividly as this time, and he felt that she had really passed through the

great change.

She still clung to his hand, yet seemed afraid to go out with him—out and

away from it. He stayed there with her all that night and all the next day,

when the darkening sun came again, and again he could not see her.

Once the well-meaning friends of his beloved disturbed her body, doing

those sacred offices which seem so necessary to the living, but which may

sorely disturb the dead.

He stayed with her the second night and all the second day. He could hear

the sobs of her grieving parents, though they could not see either him or

their daughter; but on the second night the little dog of his love came

into the room where it lay, the room in which their two souls still stood,

and the little dog saw them and whined piteously. The man could hear it,

and she also could hear it.

And now she could hear him more plainly when he spoke to her.

"Where will they take it?" she asked him.

He recalled the time when he had been held spellbound near his own

lifeless form, over which his loved one had shed bitter tears. And he

asked her if it would not be better to come away altogether; but she could

not, or thought she could not.

On the third day he knew from the agitation of his love that they were

placing her body in the coffin. After a while he felt, though he could not

see, that many other persons were in the room, and he heard mournful music.

Music can reach from one world to another, can be heard far more plainly

than human voices, which generally cannot be heard at all except by the

trained listener.

By and by his love was sorely agitated, and he also, through sympathy with

her; and they felt themselves going slowly—oh, so slowly!—along. And he

said to her:

"Do not be grieved. They are taking it to the burial; but you are safe

with me." He knew that she was much troubled.

It is not for nothing that over the house of death there always hangs a

strange hush, not to be explained by the mere losing of the loved one.

Those who remain behind feel, though they cannot see, the soul of the one

who has gone out. Their souls are full of sympathy for him in his

bewilderment.

The change need not be painful if one would only remember that it has been

passed through before; but one so easily forgets. We sometimes call the

earth the Valley of Forgetfulness.

During the days and weeks that followed this lover remained with his loved

one, ever trying to draw her away from the earth and from it, which had

for her, as for so many, a fearsome fascination.

It is said that the souls of those who have lived long on earth more

easily detach themselves; but this woman was still young, only about

thirty, and even with the help of her lover it was a little time before

she could get free.

But one day (or night, as you would say) he showed her the home which he

had built for her, and it was literally a mansion in the sky. She entered

with him, and it became their home.

Sometimes he leaves her for a little while, or she leaves him; for the joy

of being together is heightened here, as on the earth, by an occasional

separation; but not until she was content and accustomed to the new life

did he leave her at all.

During the first days the habit of earthly hunger often held her, and he